Erich Mendelsohn’sErich Mendelsohn (1887–1953) studied architecture at the Charlottenburg (Berlin) and Munich universities of applied sciences. He married Luise Maas in 1915. After returning from the First World War, he founded his own practice in Berlin – it became the best-known and most successful architecture office in Germany. In 1933 he emigrated to England, before moving to Jerusalem in 1939 and then to the USA in 1941. He built important works in all these countries. first known plan for the Einstein Tower, which came out of his sketches, was based not only on Erwin Finlay Freundlich’sErwin Finlay Freundlich (1885–1964) was an astrophysicist. In 1910 he became an assistant at the Berlin Observatory. He joined Einstein’s Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics in 1918, becoming its first member of staff. He drew up plans for the Einstein Tower, which was to be the most powerful solar observatory in Europe. He was made director of the Einstein Tower in 1920. He was expelled by the Nazis and became a professor of astronomy in Istanbul. He was offered a professorship at the German University in Prague in 1936 and fled to Holland in 1939. He then took up a post at the University of St Andrews in Scotland, where he established an astronomy department, together with an observatory. He became Napier Professor of Astronomy in 1951. technical specifications but also on a plan that was signed by Freundlich but probably drafted by engineer Martin SalomonsenMartin Salomonsen (1881–1942), engineer, studied at Polyteknisk Læreanstalt in Copenhagen. After working for Beton- und Monierbau AG in Berlin, he went freelance as a consultant engineer. Salomonsen supported Mendelsohn not only with the Einstein Tower but also with the design for the Red Banner Textile Factory and the construction of the Columbushaus in Berlin..

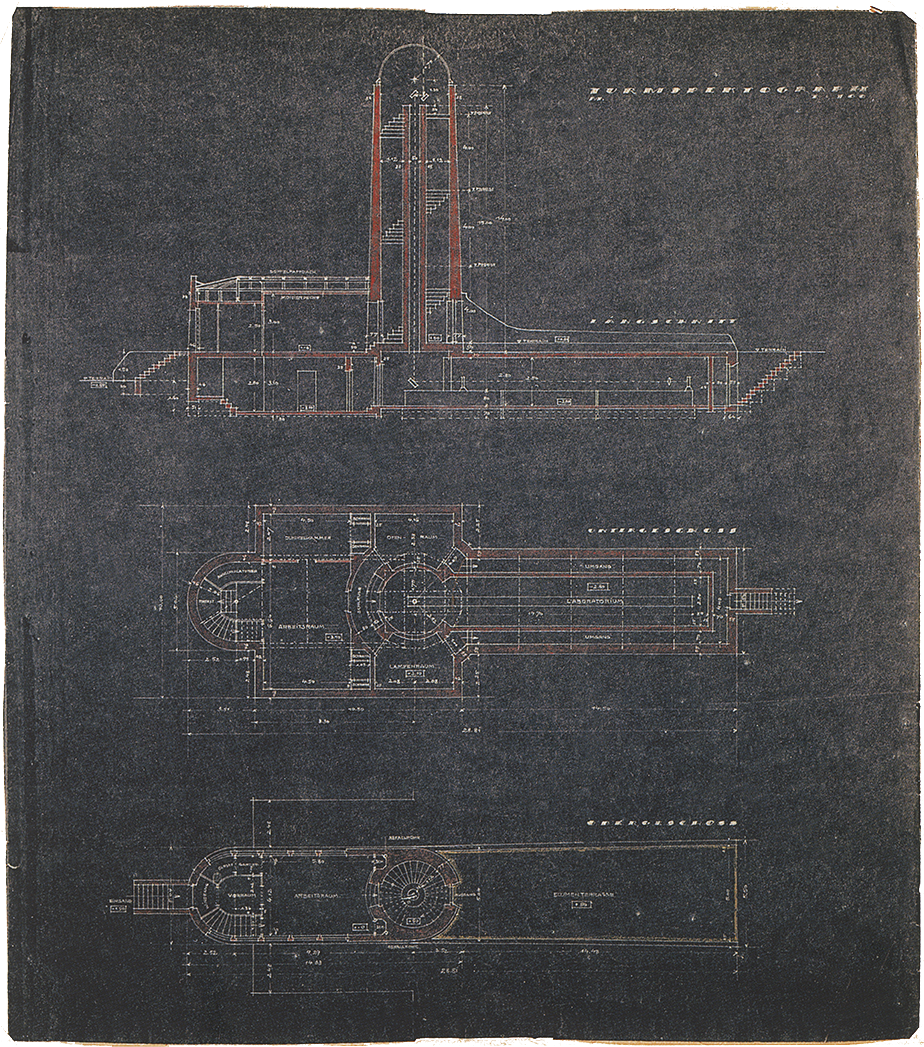

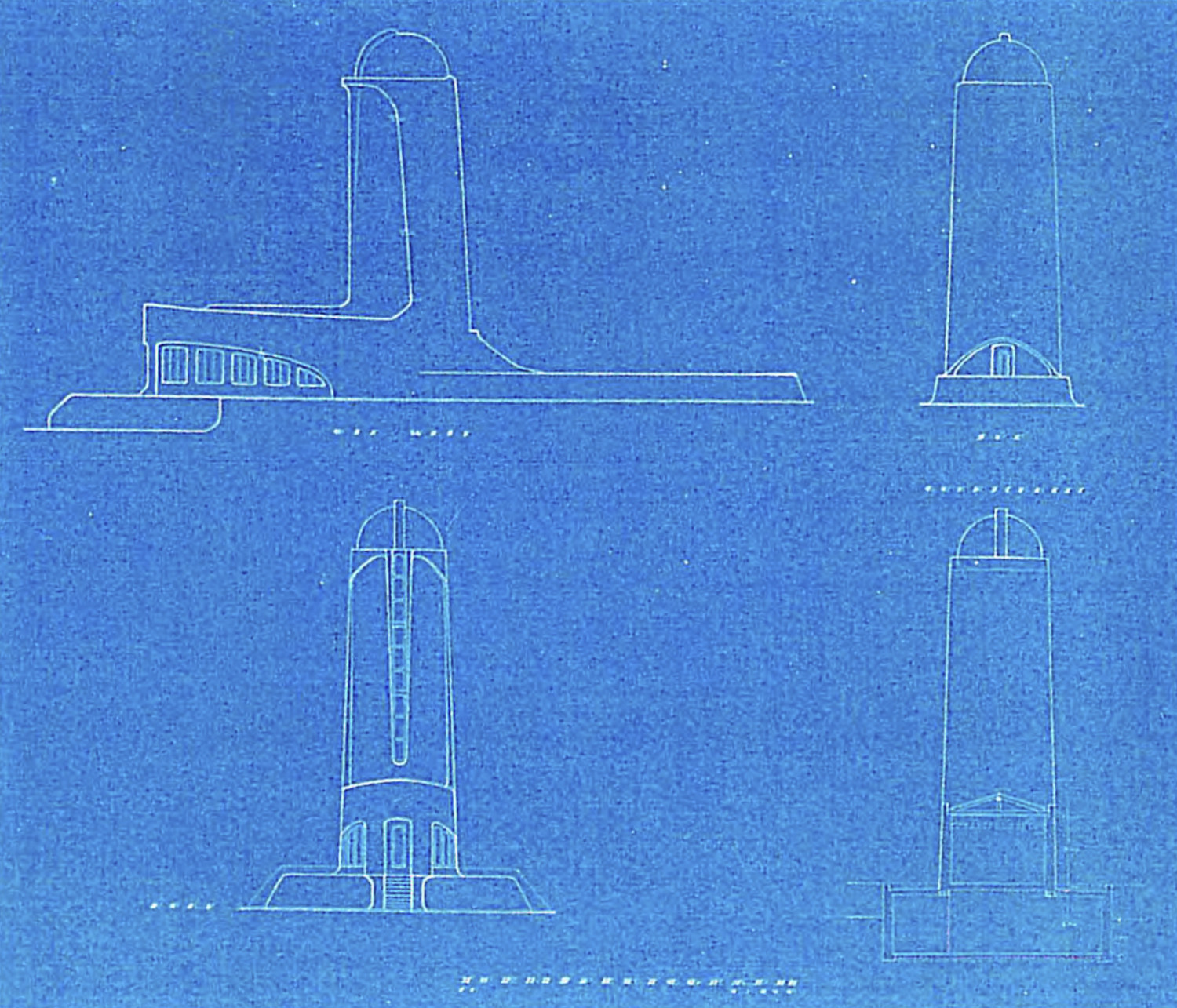

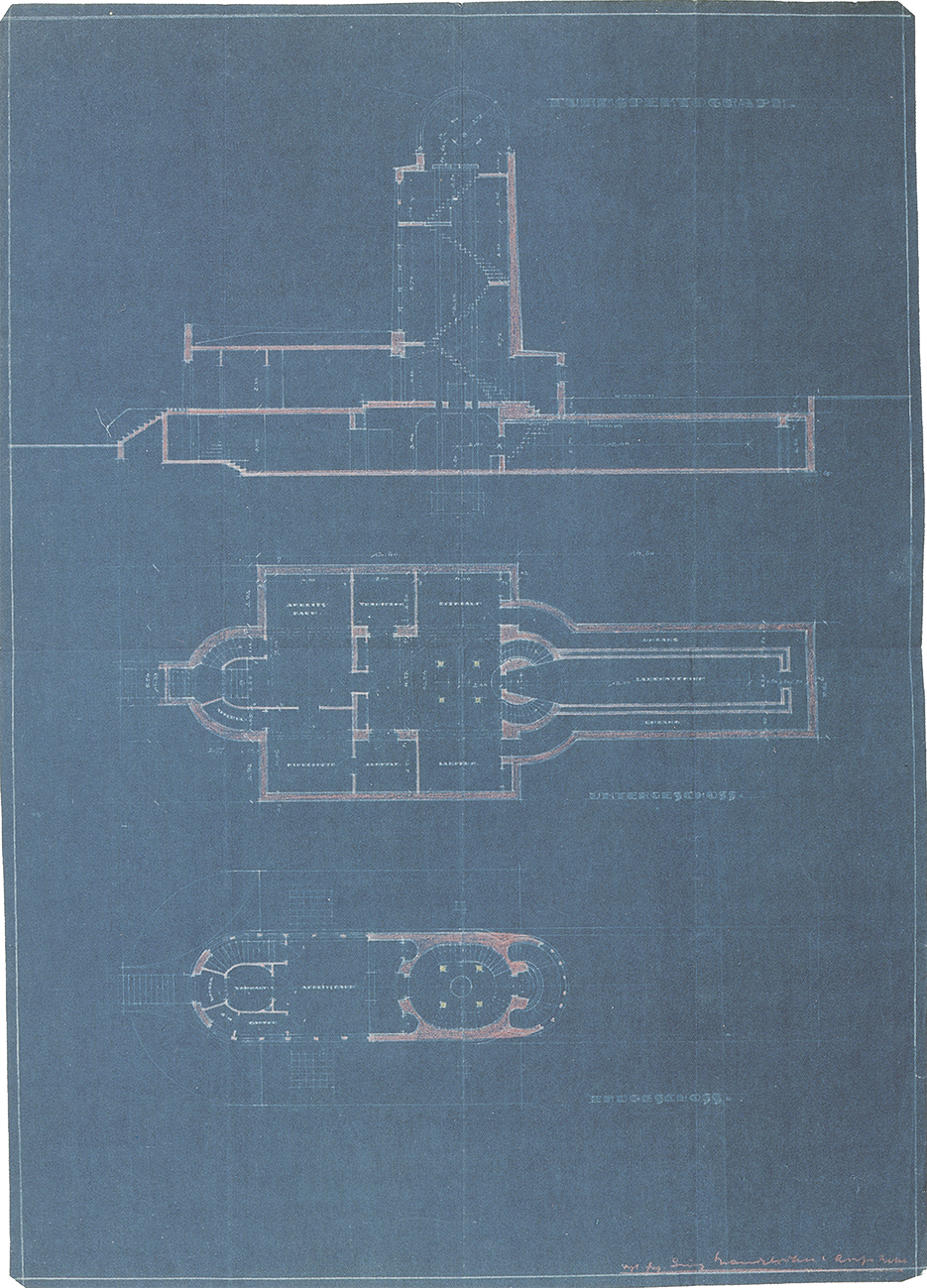

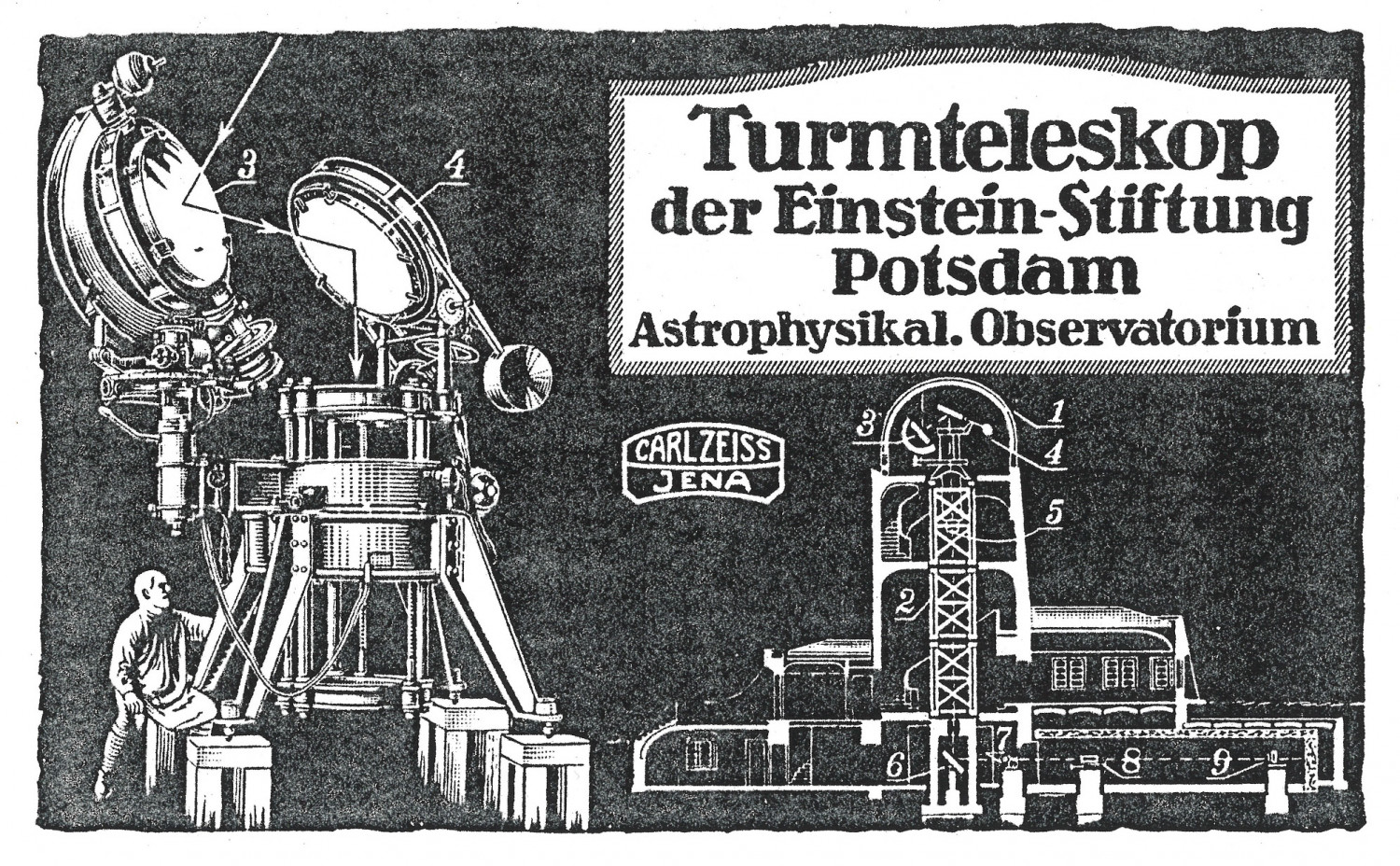

It was probably at this stage of the planning process that Mendelsohn travelled to Jena in May 1920, still waiting for an official commission. There he met with engineers from the Carl Zeiss company in order to calibrate his plans in accord with the technical requirements of the optical device, which came from Zeiss. The coelostatA celostat usually consists of two mirrors arranged in a way that a stationary telescope (e.g. a tower telescope) can be used to follow the motion of celestial bodies over the entire course of the day or night., the telescope’s upper mirror system, needed to be mounted in such a way that there would be no vibration. By the same token, the telescope’s lens could not have any contact with the stairwell or with other parts of the structure. This all meant that more space was required than Mendelsohn had previously envisaged. He had to introduce a separate tower to house the telescope’s optical system. Mendelsohn designed the actual building around this inner tower. This “tower within a tower” gives the whole building somewhat more volume than is represented in the first known plan.

Mendelsohn wrote to his wife on the subject: “On Monday morning, off through the Thuringian countryside to Jena for exhausting meetings at Zeiss. The tower is getting a somewhat stouter belly, which naturally changes all the proportions. The layout remains the same. A guided tour of the Zeiss factory revealed congruence between the basic technical elements and my vision of the optical system. Proof of the primitivity of intuition.… Hard at work now to get the Hermann factory ready for submission and prepare Potsdam for the start of construction before I come to you, sweet wife. I’m dreadfully anxious. May is wonderfully warm and calls you. Always” (Letter from Erich to Luise Mendelsohn, dated 12 May 1920). Not longer afterwards, in another letter to his wife, he wrote: “Perhaps the building will be entirely concrete after all. In light of the problem, that would be highly desirable” (31 May 1920). This is the only indication that Mendelsohn was thinking about realising the complete construction in reinforced concrete (which at the time was called ferroconcrete). There are a number of other very sparse remarks on the choice of materials, all of which refer explicitly to a composite construction method.

Given the hardship and inflation of the post-war years, there was nothing self-evident about the fact that Mendelsohn was working at the time not only on the Einstein Tower but also on his equally famous hat factory for Friedrich Steinberg, Herrmann & Co. in Luckenwalde. As with the Einstein Tower, Erich had his wife, Luise MendelsohnLuise Mendelsohn, née Maas (1894–1980), studied cello in London, Leipzig, and Berlin. She met Erich Mendelsohn in 1910 and married him in 1915. Their daughter Marie Luise Esther was born in 1916. She abandoned her musical career and supported Erich when he started his own practice. Many of Erich’s jobs, including the commission for the Einstein Tower, can be traced back to the network Luise established. After the Mendelsohn family were forced out of Germany by the Nazis, Luise secured many new commissions for her husband. After Erich’s death, she organised his estate., to thank for landing the hat factory commission. Its success meant that the office, which had been founded only two years previously, expanded too, with several architects now working for Mendelsohn, including Richard NeutraRichard Neutra (1892–1970), architect, studied architecture at Vienna University of Technology and at Adolf Loos’s architecture school as well as garden architecture in Zurich. In 1921 he began working for the Luckenwalde municipal planning and building control office and designed the forest cemetery there. He worked with Erich Mendelsohn from 1921 to 1923 and was responsible, among other things, for the landscape design for the Einstein Tower..

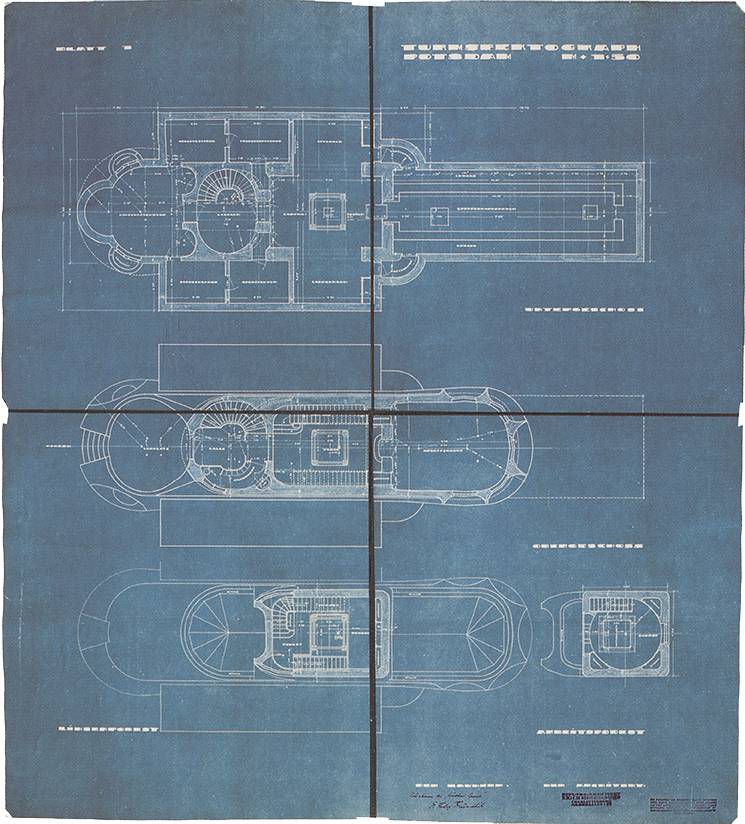

The further elaboration of the Einstein Tower then took place in close consultation with the engineers from Carl Zeiss Jena and with Siemens (at that time still Siemens & Halske, who were responsible for providing the technical equipment). This gave rise to a precursor of the second plan, which Mendelsohn presented to the astrophysicists in Potsdam in June 1919. Based on these discussions, Mendelsohn introduced glazing to the entire south side of the tower. The workroom on the ground floor was also provided with generous windowing. The floor plan is still somewhat awkward here, as the only access to the cloakroom, toilet, and basement laboratory is via the workroom. There are as yet no windows in the basement.

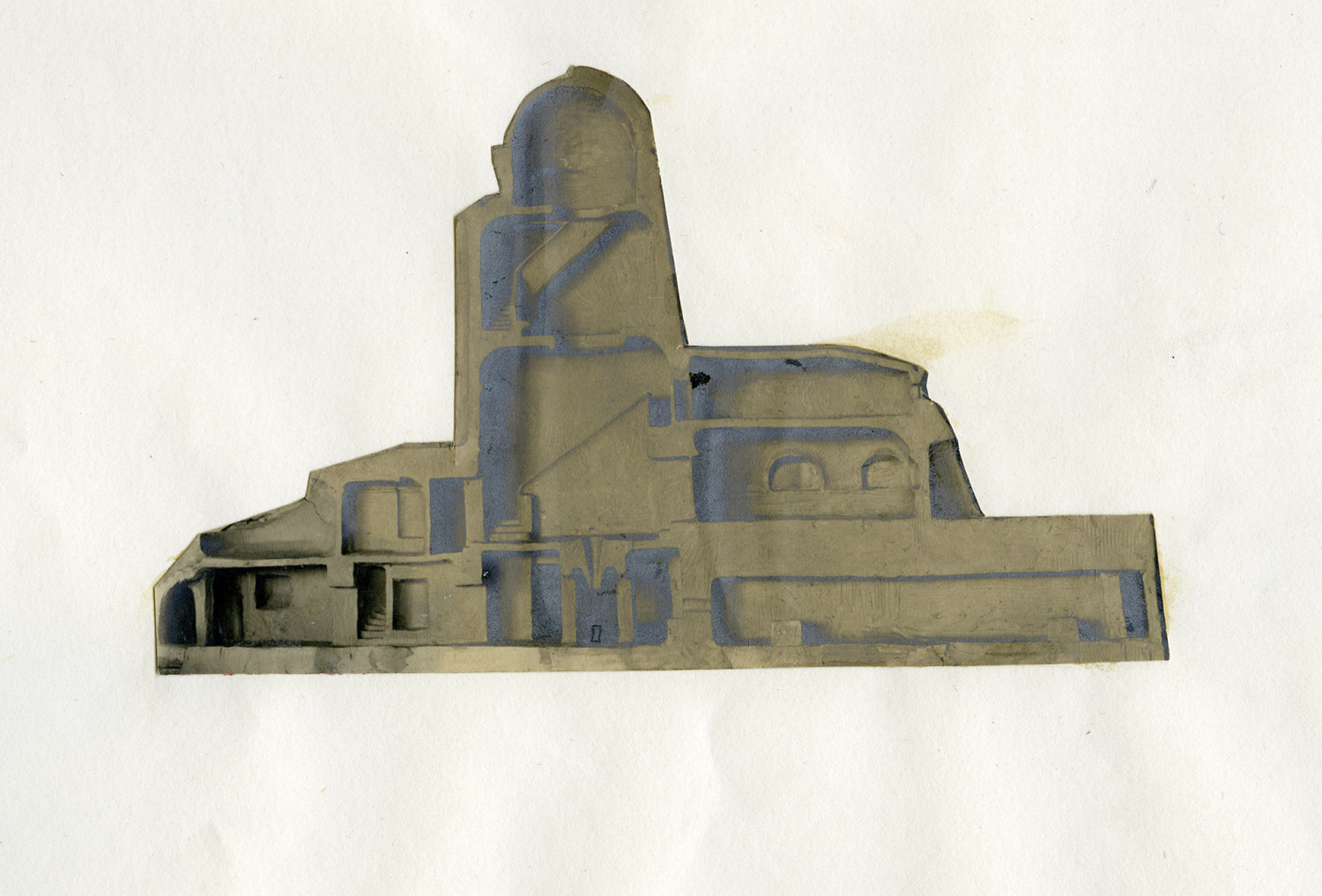

Further elaborations, especially of the inner structure, followed. Design work and implementation planning went hand in hand in a rapid succession of new plans. Mendelsohn shifted the workroom to the south side of the ground floor, where it would remain. There was still no room for overnight stays, but the arrangement of the toilet, basement access, and tower staircase had a much more functional design. In the tower, two platforms were added: one to make it easier to get to the lens in the telescope; the other, located directly beneath the dome, to allow the silvering of the heavy mirrors of the coelostat, which had to be done on a regular basis, to be carried out in comfort.

On 28 June 1920 Erich wrote to Luise concerning the status of the final draft: “We (Kaprowski and I) spent Sunday working on the tower to give it free rein. A quick forty winks in the afternoon with the vision of massaging the last sore spot into a healthy state. The tower is going to be square. This will allow it to be heaved out of the stored mass of the workroom, making its backward slant visible and revealing the struggle between the poles: the workroom and entrance to the tower shifted as the logical focus. The tower becomes the energy point, the release, the ruler holding sway between two intentions. The square floor plan saves money. The only problem is the round dome on the square tower. We’ll see about that in the detail planning.… The comparison with the first sketches hits home. Line must perish; it must become an outline of mass. Line cannot profess energy or movement, if there is no mass. Architecture is a dominion of mass. You must now decide whether it is to be rings or the undiminished = brutish wall. Freundlich is back. Zeiss is in raptures. They are giving optical equipment worth ½ million. The donation of cement and iron takes us to 350,000 – at the most pennywise reckoning. So: tomorrow morning meeting – board of trustees and architect – in Potsdam. In any event, I won’t be with you on Sunday.”

After reviewing the current state of the plans in September 1920, the building authority in Potsdam called for basement windows to ensure good ventilation and bring daylight into the laboratory rooms, thereby saving on electricity costs. Mendelsohn responded to this immediately. In addition to the cellar windows that were stipulated, the overnight accommodation above the workroom also came into being in this iteration. The only thing still missing here was the small balcony from which to view the weather conditions on the southern side. Construction began that same month, despite the fact that the final plans had not yet been drawn.